John Carpenter’s “They Live” Asks Important Questions

What are you even doing?

Have you ever glimpsed the world as it truly is? Perhaps it was a moment of profound heartbreak. Perhaps it was suddenly, unexpectedly, becoming drunk on beauty. Perhaps it was the words of a song that suddenly lifted the blinders of your mind. Whatever the cause, for an instant, or an hour, or a few days, you intuitively grasped that most things didn't matter, and that the things that did stood out like a Technicolor rainbow against the grey backdrop of life.

With this new-found sense of perspective, you felt calm and wise. Although there were things to worry or be upset about, you realized that you were under no obligation to worry or be upset. You could just be calm. It was the feeling that is crudely imitated by narcotics, alcohol and anti-depressants, but it didn't come from a bottle or pill, it came from within you.

Then, like a dream, it slowly faded. Inexorably, you were drawn back into the world, recaptured by the frantic mindset that you had so briefly and beautifully escaped.

The Desert of the Real

We all have the capacity to see clearly. There are some, especially artists, who spend their whole lives attempting to communicate in words or images their own sense of clarity. A few, like singer Leonard Cohen, filmmaker John Carpenter, or economist Martin Armstrong, succeed terrifically. Others die or go insane trying. Most, however, recoil in horror from their momentary sense of perspective. It is too alien, too disruptive. Most of all, it is too isolating. How do you relate to other people, when you see them pouring their energy into vessels that will always be empty?

Every once in awhile, an anomaly will penetrate popular culture. The movie, "The Matrix," was perhaps the most spectacular in recent memory. Using traditional science-fiction tropes as a springboard, the Wachowskis successfully presented tremendously startling ideas in a very accessible manner. Audiences instinctively responded to the concept of awakening from a world of illusion into "the desert of the real."

Just as Plato observed in the "Allegory Of The Cave," when people are confronted with a truth that conflicts with their convictions, they will first mock it, and then attack it. Psychologists call this "normalcy bias." In the case of "The Matrix," it was easy to dismiss the salient points of the narrative as just so much sci-fi hokum. At the same time, the imagery of the film was co-opted by every ideological faction under the sun. The choice between the red pill and the blue pill was turned into a choice between Christ and the devil, Republicans and Democrats, atheism and religion, men's rights activists vs. "cucks, " and any other imaginable dichotomy.

Ideology is a powerful and comforting lens. Through it, you can see only what you expect to, while remaining blind to everything else. People are willing to fight, kill and die for what they believe, even if what they believe is not worth fighting about. Indeed, most things are not worth fighting about. Most things simply do not matter. As Daniel Quinn's "Ishmael " repeatedly points out, "There is more than one right way to live." But when somebody has spent a lifetime in service to - or, in some cases, in opposition to - an ideal, they will do anything to avoid admitting that the time and effort were wasted. All too often, the justification for war is that, if we stop now, all those who have died will have given their lives in vain. In war, the only absolution for death is more death. In day-to-day life, the only absolution for lack of meaning is more lack of meaning.

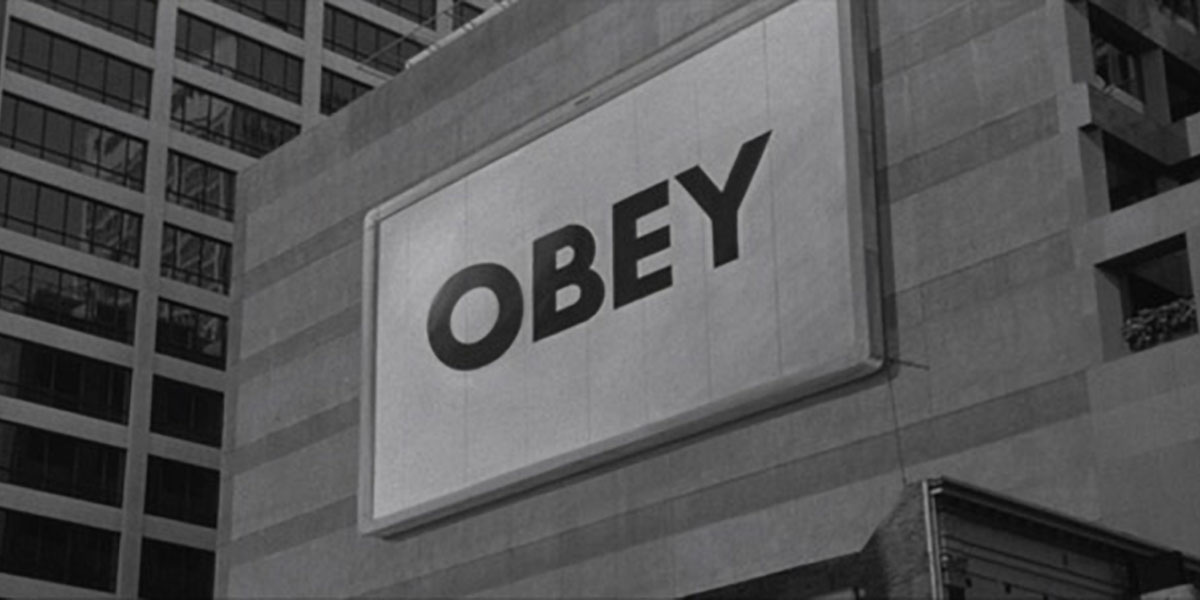

If, as in Plato's Allegory, a man has spent his life glorifying shadows, he will never admit that it was a mistake. If everything in a culture supports the notion that you should trade your hours for an endless stream of products that will always fail to satisfy you, it will take more than a sci-fi movie to jolt the inhabitants of that culture out of their behavior. It is too hard to be different. We all flatter ourselves that we would take the red pill, but in truth we all take a daily dose of the blue pill. Mass media, electronic entertainment, industrialized leisure, and especially advertising, all reinforce our ideology of complacency and consumption. John Carpenter illustrated this brilliantly in "They Live. " Wearing special sunglasses, the movie's protagonist was able to see the hidden messages surrounding him. Billboards screamed "Stay Asleep, " magazines commanded, "Watch TV, " and written on every piece of paper money were the words, "This is your God. "

At the end of another John Carpenter film, "Escape From L.A., " the hero chooses to snuff out electricity-based civilization rather than hand power back to those who had turned the world into a giant prison. "Welcome to the human race, " he growls, as the lights go out forever.

Often, this type of message is dismissed as adolescent nihilism. Nothing could be further from the truth. Rejecting the meaningless is very different from rejecting everything. Indeed, it is a prerequisite for embracing the meaningful. The challenge is determining what IS meaningful. Deep down, we all remember what is important, but there's too much money to be made by keeping us forgetful. Politicians, executives and celebrities feed us illusions masquerading as truth, and we are usually lazy enough to accept them as the real McCoy, even parroting their messages to each other on social media.

Consider the familiar refrain of "God, family and country. " There is just enough inherent value in that list to give it the ring of truth, but what they MEAN by "God, family and country " is a perversion of reality. What is important about God is not what building you worship in, it is your personal relationship with the Divine (or the Universe, if you prefer), in whatever way is wholesome to you. What is important about family is how lovingly you pay attention to each other, not how lovingly you buy things for each other. What is important about country is not which one you live in, or who runs it, but how much freedom it allows you.

Freedom is important. Beauty is important. Love is most important of all. Love is the currency of the world. When people speak of the attention economy, they are referring to love. What we pay attention to, where we put our energy, how we use our time, this is how we show what we love. This is what ideology protects, what salesman and politicians exploit, and what everyone craves.

The One Question

There is really only one question in life: Where do you put your energy? Everything else is secondary to this one consideration. Cynics like to feel clever by denigrating the idea of individual potential. "Sorry, you're NOT a 'special snowflake,'" they sneer. They are wrong. You are unique.

There is something that you, and only you, can do to make the world a better place. The challenge of your life is figuring out what it is and how to do it.

As Jim Croce sang, "There never seems to be enough time to do the things you want to do, once you find them." Like the joke about the man who drops a contact lens in a dark parking lot and looks for it under a lamppost, "because the light is better," your only chance of finding your purpose is first to stop looking where it ISN'T. The nonsense of consumer society, the politics, the gossip, the cult of personality - we call them "diversions" because we know that they divert our energy from what is important. The Dalai Lama says that the purpose of life is to increase the happiness of others. Your task is to determine the way you can best do that.

You are already awake. Do not throw good time after bad. Jettison everything unimportant, and focus your energy on what truly matters. Free yourself.

I've looked at life from both sides now

From win and lose and still somehow

It's life's illusions I recall

I really don't know life at all.

- Joni Mitchell