Why Revolutions Are Always a Surprise

It's because politicians don't study political science

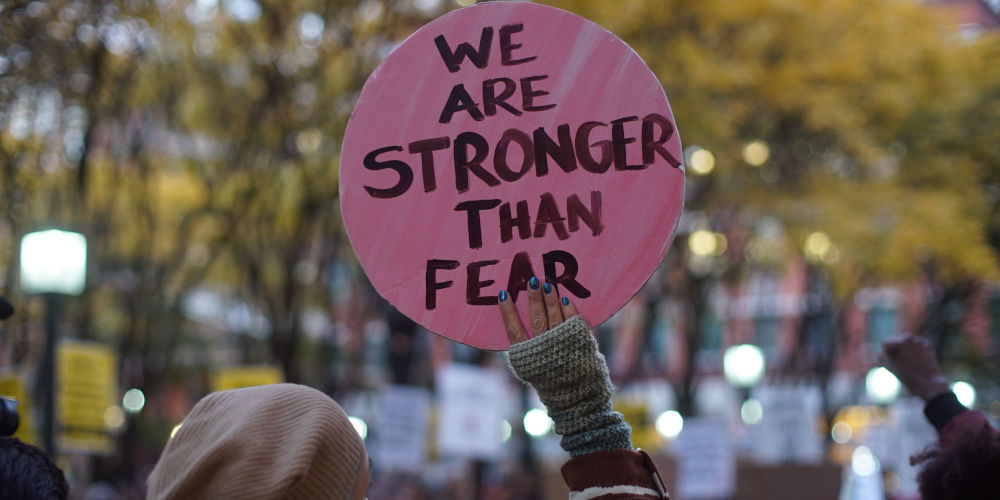

The sight of Iranian women burning hijabs in the streets of Tehran has come as a surprise to, seemingly, everyone. Who knew they felt this way? Certainly not the Iranian government. The same could be said of the Sri Lankan president, who had to watch a huge mob of his constituents party hearty in the palace he hastily evacuated before they overran it. From a sociological perspective, this is completely normal: civil unrest, mass protests, and other revolutionary activity are always as a surprise.

One day, everyone is on board with the current thing. Leaders are getting reelected, people are holding spontaneous demonstrations of support for the regime and the country seems perfectly stable.

The next day, the masses are out in the streets with torches and pitchforks, burning hijabs, or throwing bankers out of windows and hanging bureaucrats from lampposts.

How does this kind of revolution happen? More to the point, why does revolution ALWAYS seem to happen that way?

Perhaps surprisingly (given its reputation as a bullshit degree for frat boys), political science has a tidy explanation. It involves three concepts: preference falsification, revolutionary threshold, and revolutionary cascade

Preference Falsification

Imagine, if you can, that you live under a repressive, authoritarian regime, in which you don't feel comfortable expressing your dissatisfaction with the powers that be. Perhaps there are negative social consequences to sharing your opinion, maybe you would face retaliation by your employer, or maybe even armed government agents would arrive at your door with trumped-up charges of some kind. These things happen in totalitarian states. Maybe you can think of some examples.

Anyway, under such circumstances, if someone were to ask how you felt about the folks in charge, you might be inclined to fudge the truth a little bit. Or a lot. You might say that you love the comrade leader and everything he's doing, even though you hate him and his ideology with every fiber of your being.

That tendency is called preference falsification. The more repressive the regime, the more unwilling people are to say they dislike it. That's why dictators tend to enjoy such high approval ratings. It's not only that the pollsters are lying, the people they poll are lying too.

Preference falsification does a couple of things. First, it creates an illusion of consensus, which is amplified by propaganda and censorship. No matter how many people hate what's going on, each one feels that they are the only one.

Solomon Asch's famous experiment on conformity showed that a solid 30% of people will knowingly lie about their opinion, just to avoid being the only person in a group who disagrees. Add real repercussions, like the threat of prison, or violence against your family, and that number goes way up.

Secondly, widespread preference falsification means that nobody really knows how anybody else feels. This applies to both dictators and their subjects. The truth will not be revealed until people hit their revolutionary threshold.

Revolutionary Threshold

As Thomas Jefferson wrote in the declaration of independence, "all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed." In other words, people will put up with a lot of crap for a long time before taking action to overthrow their rulers.

The boiling point, if you will, is called the revolutionary threshold. Importantly, revolutionary threshold is not directly a measure of an individual's dissatisfaction; rather, it is a measure of how large a protest needs to be in order for the individual to participate.

A dissident like Vaclav Havel has a very low revolutionary threshold - requiring a coterie of zero in order to take a stand. Other people might need to see thousands of their countrymen in the streets before they have enough courage to join in.

By measuring ("operationalizing") revolutionary threshold in this way, political scientists can mathematically estimate the likelihood of a revolutionary cascade.

Revolutionary Cascade

In simple terms, a revolutionary cascade is when a protest keeps getting bigger, because the bigger it gets, the more people join in. Technically, this requires that the participating individuals have revolutionary thresholds that are fairly closely spaced.

Think of it this way: ten people show up for a protest. Their revolutionary thresholds are less than 10, so they all stay. Ten other people pass by, but their revolutionary threshold is 11, so since there are only 10 people protesting, none of the new people join in. Thus, it's fairly easy for the regime's security forces to crush the 10-person mob.

But, what if just one of the passersby had a revolutionary threshold of 10? He would join the protest. Then the other nine people - all of whom have a threshold of 11 - would join as well. Now, there would be 20 people protesting. Anyone with a revolutionary threshold of 20 or less would now join in. And so it goes, until there are too many people for the police to effectively manage.

Of course, in practice, it's not quite so neat and tidy. A wide variety of factors can influence a person's revolutionary threshold from one day to the next. Nonetheless, it's a very useful way of explaining how some protests fizzle out and others turn into gigantic riots.

So, when will the people rise up and overthrow their rulers? Nobody can say for certain, but we can expect it to be both completely surprising and simultaneously completely predictable.