Build a Minimalist First Aid Kit for Pennies

Be frugal AND prepared

How do you reconcile the "two is one, one is none" mentality of emergency preparedness with a desire for budget-friendly minimalism? The short answer is: the more you know, the less you need!

An even shorter answer is: when in doubt, ask an expert. Why? Because even if you DON'T know, they DO!

A perfect example of this is the humble First Aid kit. There are countless variations of them, both improvised and manufactured, and one could easily become overwhelmed trying to decide what to include (and how to pay for it all!). As is usually the case, a little bit of knowledge can replace a lot of gear.

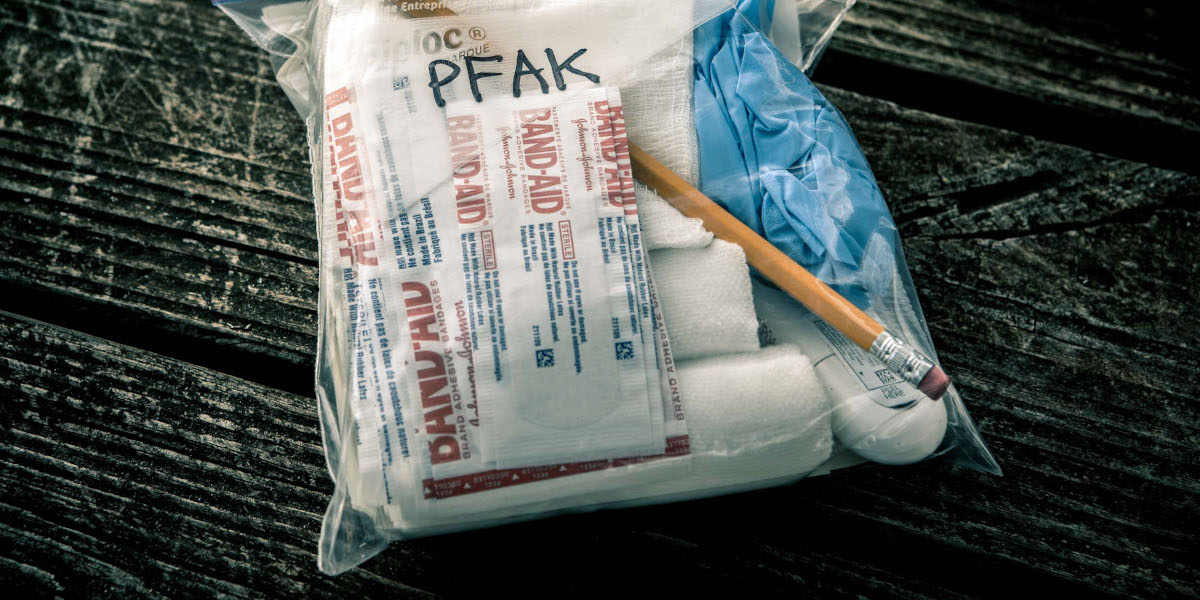

Most commercially-available first aid kits are either stocked with low-grade supplies that are useless for anything more serious than a splinter, or military-grade PFAKs (Personal First Aid Kits) at wallet-busting prices. I've been refining my own home-made kits for years, but since I (fortunately!) don't have to play the Good Samaritan very often, I was delighted to see the following advice from an experienced paramedic. This appeared in the print-only version of the January 2018 "American Shooter" magazine, and it's so great, I'm going to copy it here in its entirety (at least until somebody tells me to take it down).

I retired after 30 years as a firefighter-paramedic and used to carry a very expensive kit stocked with just about every clever medical adjunct made for emergencies. Over time, I've found the primary thing I've needed off duty was a wound pack: I place a 3- to 4-inch-thick stack of non-sterile, 4x4 sponges, one 3- to 4-inch-wide roller gauze, some Band-Aids, a new pencil for cinching a tourniquet (TQ), sterile 4x4 dressings for final bandaging and some nitrite gloves-all in a 1-quart plastic bag. You can make these for $2 to $3 a pack. The sponges work for direct pressure, and I stack more on as needed. The roller gauze can be tied as a pressure bandage or used as a TQ with gloves to provide barrier protection. I've only applied one TQ in 30 years-otherwise I've never encountered bleeding I couldn't control with direct pressure, arterial pressure and elevation. I'm sure TQs are commonly needed where high explosives are found or when you can't focus all of your time on bleeding control, but in non-combat zones, I just don't think you need to drop $20-$30 on a specialty TQ. I have two or three of these packs in every car, building and pack/ bag that I own.

I subscribe to keeping it simple (be highly prepared for high-probability injuries, and adequately prepared for low-probability injuries), and It really doesn't have to break the bank. If you keep the costs reasonable you can build multiples of these "elaborate" kits for different locations and don't always have to remember to grab the "good one" when you leave. And, of course, you need training to know how to use it all.

I would add two caveats to this outstanding recommendation. First, paramedics don't generally worry about disinfecting wounds because they are sending injured people directly to the hospital, where everything will be cleaned thoroughly. If you anticipate using your first aid kit for times when a trip to the hospital is either impossible or unnecessary, you'll want to include some kind of antimicrobial ointment or spray to reduce the likelihood of infection. Secondly, although the author doesn't mention it, he almost certainly carries some kind of multi-tool – either a specialized one like this, or a general-purpose one like this – for cutting rope, fabric, seatbelts, and extracting small objects.

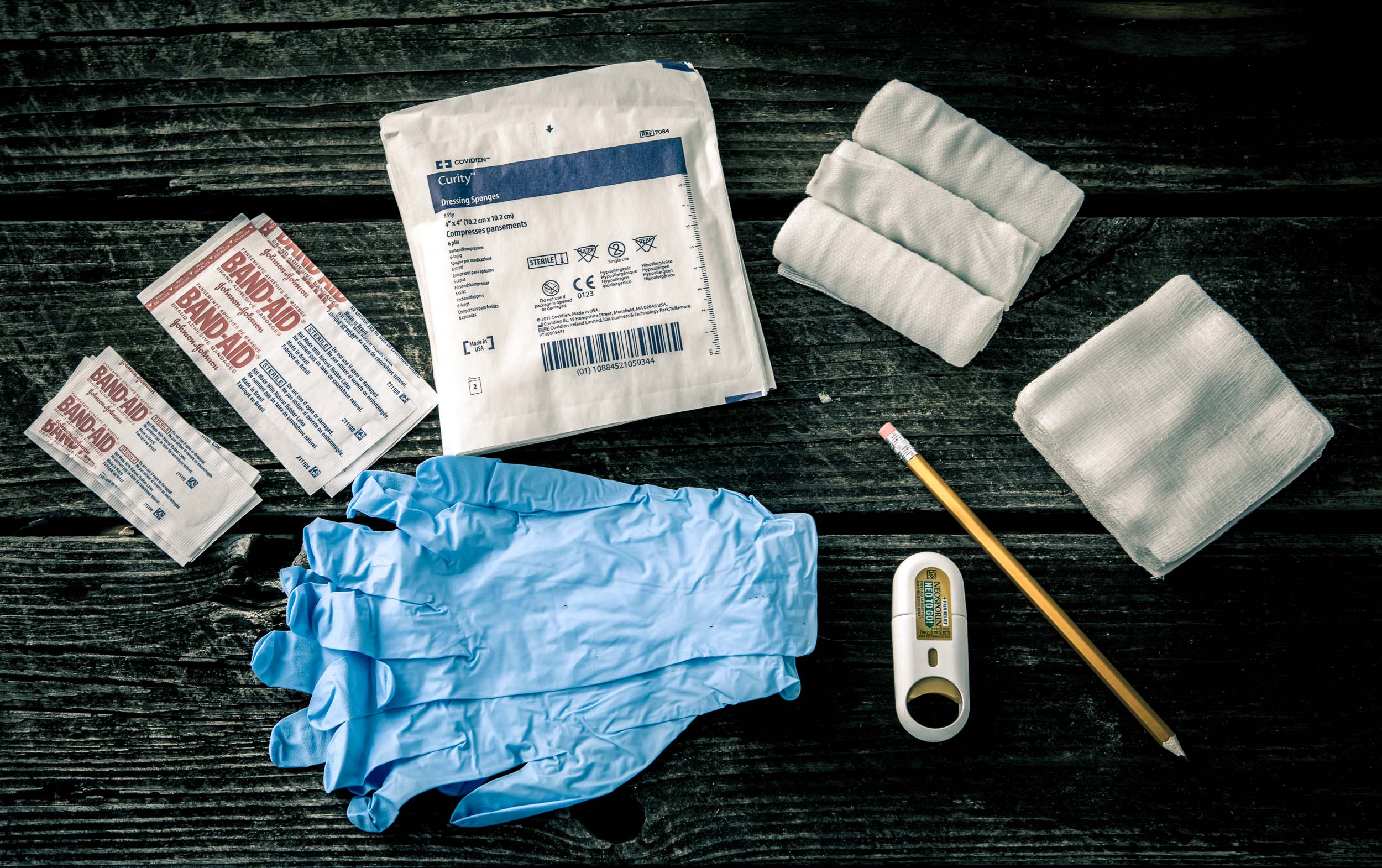

With that said, here are the components of the kit:

- Sterile 4x4 Dressing

- Non-Sterile 4x4 Sponges

- 4" Roller Gauze

- Nitrile Gloves

- Pencil

- Band-Aids

- Antibacterial Spray

- 1-Quart Ziploc Bag

I strongly suggest getting the waterproof "Tough Strip" Band-Aids. They cost a little more, but they won't fall off as soon as they get wet, which makes them more than worth the difference in price, especially when used on the hands.

This is what the components of one kit look like.

Of course, as the original writer pointed out, "you need training to know how to use it all!" In many places, CERT (Community Emergency Response Team) classes are offered free of charge by local emergency management offices, and those classes cover a lot of emergency first aid, including proper use of tourniquets and the type of bandages that this kit contains, as well as non-bleeding issues such as shock and airway obstruction.

Remember: the more you know, the less you need!